by Jonathan Rudnicki

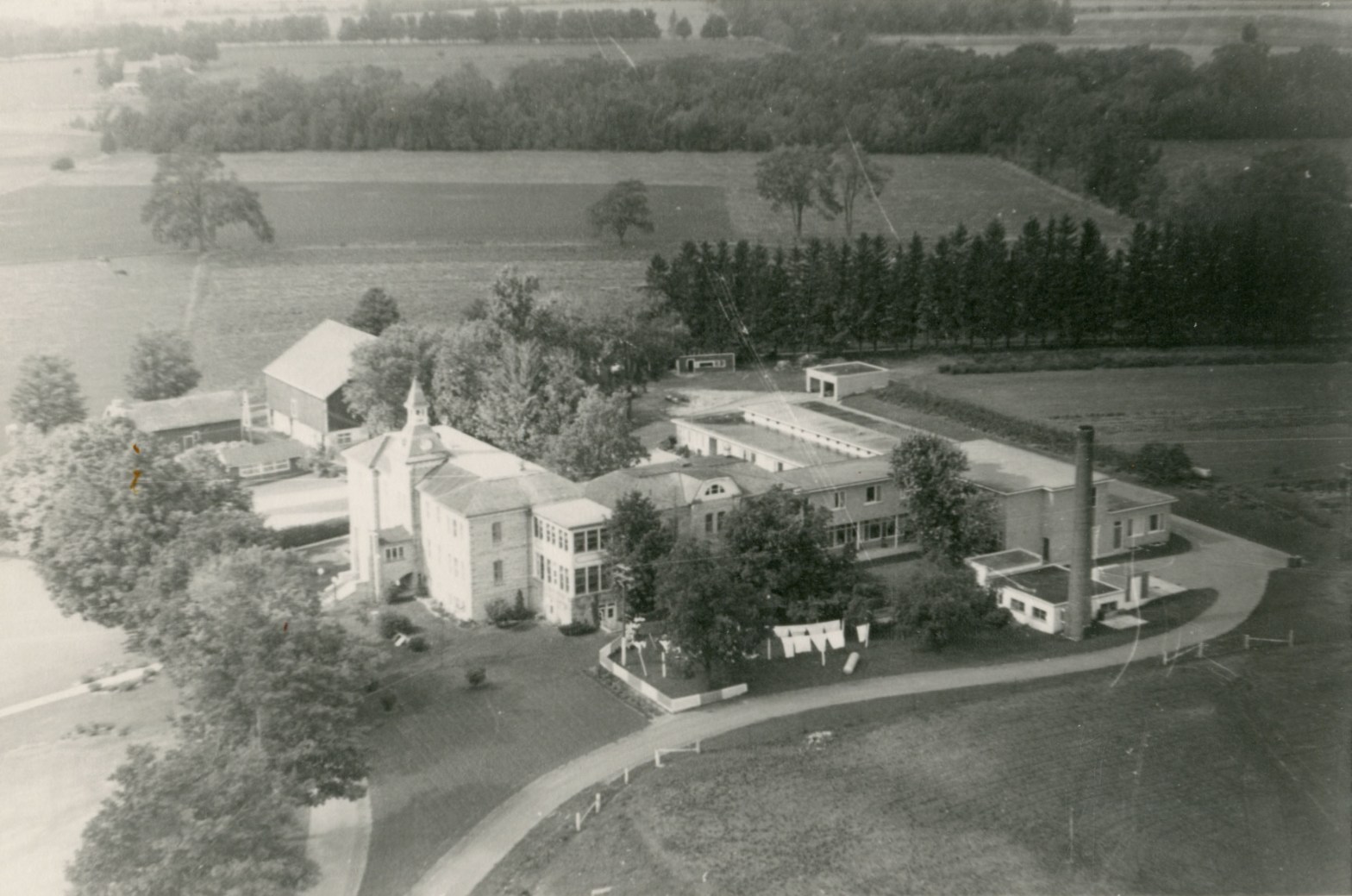

Aerial photograph showing site of the Wellington County Home for the Aged, around 1960. The oldest surviving 19th-century Ontario “house of industry”, the building now serves as a museum and county archive just outside of Fergus, Ont. But it recalls the era when the province’s poor, ailing and old were warehoused in drab facilities to live out their days. Today’s problem-plagued long-term care system in Ontario retains some characteristics of the old poorhouses of the 1800s [Wellington County Museum & Archives, ph 2863.]

My maternal grandmother’s new apartment is on the ground floor with a large window that looks out into the parking lot. It’s slightly smaller than her previous place, but it’s only a five-minute walk from my mother’s home in Ottawa — much closer than the previous place in Montreal.

Since the death of her husband, Grant, my family has helped my grandmother, Eleanor, gradually downsize her living situation in Montreal. First, we helped her move from the apartment they were living in to a smaller one. Then she moved to an assisted-living apartment complex. And now we’ve moved her to another, smaller retirement residence in Ottawa, so our family can be near.

Throughout the pandemic, there have been times when she has lived with my family to keep her isolated and safe from COVID-19. She enjoyed it for a time, but eventually she wanted to go back to her apartment.

My mother found it difficult to strike a balance between caring for her elderly mother while supporting her independence and dignity.

It was a struggle to stay connected with my grandmother when she was living in Montreal. She’s quiet and doesn’t want to be a burden on my family. At one point, when she became sick with COVID-19, She didn’t even tell my mother because she didn’t want her to worry. My mother went to visit her in Montreal and found her lying in bed, shivering under the sheets with a fever.

My grandmother is the last of my grandparents who is still alive. At 87, she is frail, hard of hearing and moves about precariously with a walker or cane. Soon she might need the services of a long-term care home, like my father’s late mother, and many other older Ontarians who can no longer live on their own because of the frailties of age.

My family certainly isn’t the only one facing the challenges of ageing. Thousands of older Ontarians are in need of important services, and that number is slated to only get bigger in coming years. According to Statistics Canada, by 2046, the population aged 85 and older could triple what it is today, coming close to 2.5 million people. For many, long-term care homes are the only option for individuals who cannot care for themselves. And for decades it has been the go-to living arrangement for ageing Canadians who need 24-hour, seven-days-a-week supervised medical care. But in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated to the Canadian public that the current long-term care system is not good enough. The waitlists to get into any long-term care home are frustratingly long. It can take years to get in depending on the region. And even then you don’t always get to choose which facility you’re going to.

In April 2020, the Canadian military arrived at five different long-term care homes in Ontario to provide humanitarian and medical support as outbreaks of COVID-19 spread rapidly and devastatingly in facilities across the province. According to observations made by the military, conditions and services in many instances were so poor that many of the reported deaths in these homes could be attributed to neglect. One Canadian Armed Forces member is quoted in the report as saying, “It’s heartbreaking to get a report about someone who is ‘agitated and difficult’ and has been getting PRN narcotics or benzodiazepines to sedate them, but when you talk to them, they just say they’re ‘scared and feel alone like they’re in jail.’”

The COVID-19 pandemic pulled back the curtain on a host of problems plaguing long-term care homes in Canada, showing the public what many experts and advocates have been warning us for decades: this country’s long-term care system is failing its residents and their families.

“A lot of the system has been traditionally rooted in charity and poverty and not really emphasized on providing people care,”

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research, National Institute on Ageing and director of geriatrics at Mount Sinai and the University Health Network Hospitals, Toronto

Many homes work with a limited budget. Many long-term care workers are only hired on a part-time basis, which means they need to work at multiple homes to make a living (this proved to be disastrous during the pandemic, spreading the virus between homes). Not enough beds means overcrowding, with as many as four patients to a room. And over the years there have been many instances of abuse or neglect. In 2020, CBC Marketplace analyzed more than 10,000 inspection reports from Ontario’s long-term care homes and found that of the 632 homes in the Ontario database, 85 per cent were “repeat offenders” of the Long-Term Care Homes Act and Regulations between 2015 and 2019. Some of the violations include physical abuse, poor infection control, and poor skin and wound care.

Dr. Samir Sinha is the director of geriatrics at Mount Sinai and the University Health Network Hospitals in Toronto, as well as director of health policy research at Toronto Metropolitan University’s National Institute on Ageing, a think tank working to develop what it calls a National Seniors Strategy.

“A lot of the system has been traditionally rooted in charity and poverty and not really emphasized on providing people care,” said Sinha, who added that the focus has been “really kind of containing people and giving them a place to live, if you will, as opposed to a place where they can actually live.”

Sinha called this containing of older people warehousing and said it shouldn’t be the organizing principle of long-term care in the 21st century. But right now, Sinha says, the Ontario government seems to think it should be.

“When you start to think about (containing people) as a deep underlying construct, that really underpins a lot of the thinking and the reasoning. You start to understand why we have these industrial complexes, these warehousing spaces where you now have (Ontario Premier Doug Ford) running around the province in hospital parking lots showing a 320-bed new home that’s been built using modular construction methods.”

Lakeridge Gardens is the first long-term care home to be built under Ontario’s Accelerated Build Pilot Program and, on its website, boasts about its modern and safe environment for residents and its high-quality, resident-centred care.

During the program’s launch in July 2020, Ford said: “Our government won’t accept the status quo in long-term care. We made a commitment to seniors and their families to improve the quality of Ontario’s long-term care homes, and we intend to follow through.”

The pilot program was meant to accelerate the development of long-term care homes at a time when Ontario – along with the rest of Canada and the world – was grappling with the early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. And it worked. Lakeridge Gardens was built in an impressive 13 months, with construction complete in the winter of 2022 and opening to residents in March 2022.

But does simply building more space for beds really improve the quality of Ontario’s long-term care homes? Sinha doesn’t think so.

“You take a look at the video they shot in the home and it honestly looks like a prison. But you get a quilted bed sheet and a little side table. It really doesn’t look that much different than an old prison type thing. Anybody who sees that video doesn’t tell me ‘that’s where I aspire to end up living.’”

The underlying construct of warehousing people is a tradition in Canada, going back well over a century to Victoria-era institutions like the poorhouse, homes dedicated to housing society’s destitute souls. It was a good solution at the time, said Hailey Johnston, curator at the Wellington County Museum in Fergus, Ont., a heritage building that preserves the oldest surviving rural poorhouse in Canada, established in 1877.

“What we hear from people so often is, wow, thank goodness things have changed. And other people say, wow, well times haven’t really changed much. And I mean, both people are correct,” said Johnston.

The poorhouses of Ontario, which would later be officially dubbed “houses of industry,” were designed to provide basic shelter to people who were unable to work. In the beginning, this meant anyone from orphaned children, women who became pregnant out of wedlock, people with disabilities, and the elderly who had no one to support them.

“It was really the beginning of institutional relief,” Johnston said. Before the poorhouses, communities would take care of their poor through outdoor relief, or informal charity, like leaving someone firewood or passing a motion at city council that would help pay for an individual’s groceries if they needed it.

This form of relief didn’t stop when poorhouses began, said Johnston, “There were communities that decided based on the individual scenario the best way to help a person would be to keep them in their home and the town sends someone to fix their roof, or whatever. Or they decide, no, we’ll send them down to the house of industry.”

Over time, more specialized types of homes began to appear in Ontario; for children, people with disabilities, and destitute women. The “inmates” left in the houses of industry gradually became older until, in 1947, Ontario passed the Homes for the Aged Act. The legislation would turn every house of industry in Ontario into a home for the aged. The Wellington House of Industry and Refuge, for example, became the Wellington Home for the Aged.

As time went on, improvements in medical care and training for staff modernized how the elderly were cared for and the practices evolved into a provincial system that would come to be known as long-term care. But the heritage of the earlier poorhouse operations remains expressed in the present day.

“The richer you are, the more options you have when it comes to long-term care,” said Sinha. “Historically, we developed our long-term care system as a safety net system. But it’s quite limited in terms of what it offers for the people who have no choice but to rely on that system.”

“Prioritizing the pursuit of profit over provision of high-quality care is a fundamental reason why housing conditions, levels of care, infections, and death rates have been worse on average at for-profit facilities.”

From the 2022 report Careless Profits by the non-profit Canadians for Tax Fairness

What Ontario’s system currently offers has been thoroughly criticized for its lack of fundamental care, shortages of crucial staff, and a waitlist more than 38,000 names long as of May 2021. In May 2022, the non-profit Canadians for Tax Fairness released a report estimating that private, for-profit long-term care companies (which account for 57 per cent of the LTC homes in Ontario) diverted $4 billion in potential public funding into shareholder pockets instead of improving care for residents. In recent years, that means $400 million annually that could have gone towards lowering death rates, according to the report, meaning an estimated 1,400 fewer residents would have died in 2020 as COVID-19 ravaged the province’s long-term care facilities.

“If the funds that were diverted into profits had been spent to improve care, much death and suffering during the pandemic could have been prevented,” the report reads. “Prioritizing the pursuit of profit over provision of high-quality care is a fundamental reason why housing conditions, levels of care, infections, and death rates have been worse on average at for-profit facilities.”

How do you fix a broken system? It starts with advocacy and public support, and Sinha says that shift is happening now. One of the reasons for that, Sinha said, is Canada’s ageing population.

“Over the last decade, since our baby boomers started turning 65, it is very interesting watching how successive political parties and governments and elections are actually increasingly pandering to older adults and their needs,” said Sinha.

By 2030, close to one in four Ontarians will be over 65. That’s a lot of potential voters who will be wanting political support for improved elder care in the province.

“I do think things are shifting,” said Sinha. “It’s mainly because finally society is demanding that this becomes a priority, but it’s a priority that will shift against a really deeply ingrained societal ageism.”

That ageism, Sinha added, reflects “a longstanding tradition where we have warehoused older people as opposed to providing them dignified places in which they can age in place.”

This shift is coming with a variety of innovations in elder care that herald potentially transformative improvements to the current system. Some inspiration comes from other countries, such as Denmark, which has developed a strategy of moving ageing people into smaller, more accessible, more comfortable apartments.

“They’ve shown that that’s a really nice solution for a lot of people, where they can still age in their communities but in a dwelling that allows them truly to just age in place,” said Sinha.

The Netherlands has also developed the concept of the “Hogeweyk,” or Dementia Village, which reimagines a typical long-term care institution as a self-contained living and breathing community. It’s designed to look and function like a village with shops, cafés and parks.

This inspired Providence Living, a Vancouver-based not-for-profit organization, to bring the first publicly-funded long-term care home based on the concept of a dementia village to Canada. In the Vancouver Island town of Comox, B.C., Providence Living began construction on the project in June 2022 and hopes to complete it by 2024.

Candace Chartier was CEO of Providence Living until late June 2022, when she left the position to return to Ontario to care for her own ageing family members. In an earlier interview, she said the planned Comox community based on the Dutch model isn’t a one-time project: “It’s what our model is going to be moving forward.”

A second village in Vancouver and a third village elsewhere in B.C. are being planned, too, Chartier said.

Chartier admits that simply changing the way the building is designed isn’t enough. But she said Providence Living is prepared. “The whole model of care concept is going to change, as well. That means changing the work streams, changing the policy, the procedures — like everything.”

Sinha said the model has potential for creating more dignified spaces for long-term care residents, but wants to see it in operation before he believes it. “All places should be designed to be dementia-friendly environments as opposed to, say, purpose-built dementia villages. So, how do you make sure it’s not a gimmick and (is) truly a fundamentally different form of care?”

A Broken System

My grandmother on my father’s side, Simone, died in 2018. Two years earlier, in December 2016, my father and I visited her in her room at St. Louis Residence in east-end Ottawa. The 198-bed long-term care home is situated near the Ottawa River and surrounded by trees, a verdant screen between the building where my grandmother lived and the Orleans suburbs beyond.

A tall metal cross reached up from the roof, glinting in the winter sun. St. Louis Residence was founded by Élisabeth Bruyère, a member of the Congregation of the Grey Nuns of Montreal who came to Ottawa in 1845, then called Bytown, with a mission to establish charitable services for the poor and aged.

The nuns have long since been replaced by nurses in colourful scrubs and personal support workers, professional caregivers who shuffled about the facility, smiling and nodding politely as we walked through the white and beige halls.

Medical equipment stood in the central area next to a desk where a woman was behind a computer. The air was stuffy and smelled sour, as if stale chemicals were used to wash the floors and walls.

In her room, my grandmother sat in a black wheelchair with her eyes closed. My father told me her dementia was getting worse. She looked so small sitting there, a far cry from the always smiling, always chatty grandmother I knew from my childhood. Around her room were a few pieces of familiar art and knickknacks that were brought with her to remind her of the home she’d lived in before St. Louis — to fill up the blank, beige hospital walls.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, four years ahead of the long-term care nightmare that was revealed to the Canadian public in the early months of the global pandemic, that place along the Ottawa River was not one I enjoyed visiting. It seemed like little more than a holding cell for criminals awaiting conviction. In this case, though, the inmates are a city’s beloved elders waiting for death.

COVID-19’s rampage through long-term care homes in early 2020 exposed holes in the system that would allow thousands of residents to unnecessarily die. The Canadian Armed Forces report outlined many egregious descriptions of neglect, including residents left in soiled diapers or fitted with feeding tubes containing spoiled and unchanged contents.

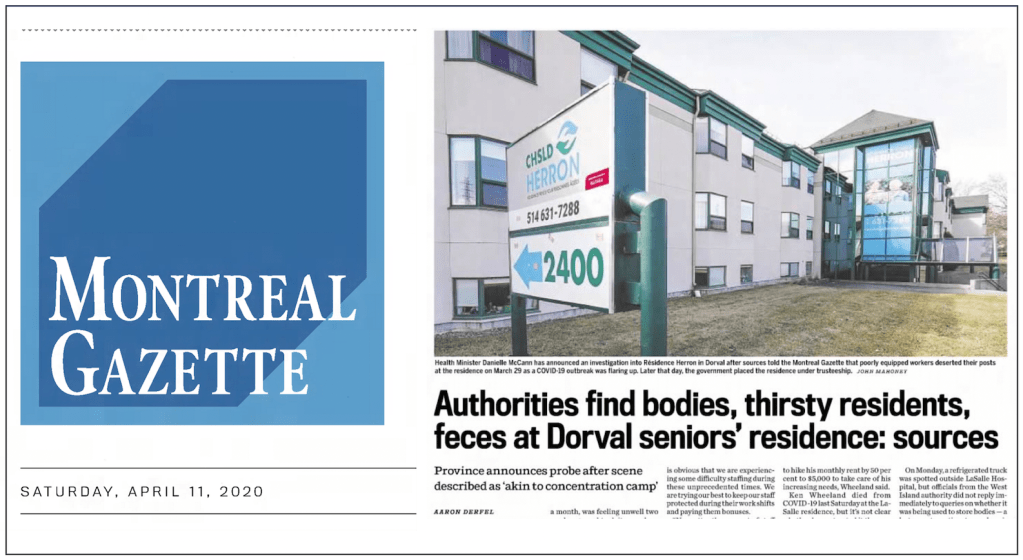

The awful reckoning around long-term care homes didn’t only happen in Ontario. In Quebec, the Montreal Gazette famously quoted health professionals describing the scene at a Dorval long-term care home as akin to a “concentration camp”.

But the glaring gaps in Canada’s elder-care regime existed well before the pandemic. Activists, nurses and doctors have been identifying cracks in the system for decades — a system in which patients can barely afford to pay for their spartan accommodations and the level of care they receive is worryingly low.

This country’s long-term care system was slowly deteriorating until the pandemic kicked it off a cliff.

In Ontario, long-term care homes are either for-profit or not-for-profit. For-profit homes allow for the shareholders and owners to pocket the profits, meaning there is little money being reinvested back into improving the home, enriching the quality of life and care for residents or increasing pay enough for employees to incentivize devotion to duty or even retention.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, as of March 2021, there were 627 long-term care homes in Ontario. Fifty-seven per cent are owned by private for-profit organizations, 27 per cent are owned by private not-for-profit organizations and only 16 per cent are publicly owned.

The current system, the branch of care that’s getting provincial funds, is one that prioritizes warehousing people rather than providing them with the care they need to live a dignified and productive life. Experts say this is a societal mindset that needs to change.

In his 2021 book Neglected No More, André Picard — the award-winning health reporter and columnist for the Globe and Mail — writes about the troubling revelations in long-term care homes made during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic by provincial health agencies.

It wasn’t long after, on April 11, 2020, that a bombshell news article from the Montreal Gazette described harrowing scenes at Residence Herron in Dorval, Que., a long-term care facility where abandoned and helpless men and women were covered in their own feces, suffering dehydration and showing other signs that they hadn’t been cared for in days. Public health officials even found two bodies that had been left in their beds.

One employee said as many as 27 residents had died in two weeks because of an unchecked coronavirus outbreak. The disturbing revelations sparked an immediate reaction from the Quebec government, which quickly launched an investigation into what had happened.

“Patients observed crying for help with staff not responding for 30 mins to over 2 hours.”

A line from the report written by Brig.-Gen. C.J.J Mialkowski after the Canadian military was sent to Ontario LTC homes to provide emergency medical aid in 2020.

Picard writes that workers in Canada’s long-term care facilities were not prepared for COVID-19, did not have proper PPE — personal protective equipment — and feared for their own safety. As shocked Canadians learned in the case of Residence Herron, many long-term care employees simply stopped showing up for work, abandoning dependent residents. Near the end of April 2020, Quebec Premier François Legault asked the Canadian Forces for medical and humanitarian aid in the province’s long-term care facilities.

Ontario similarly sent in the army to support its homes for the elderly. The eye-opening result of this emergency deployment was a memo addressed to Harjit Sajjan, then Canada’s minister of national defence, in which Brig.-Gen. C.J.J Mialkowski outlined what the military observed in five Ontario long-term care homes.

The memo reads like a litany of a resident’s worst nightmares. Numerous “poor standards of practice” were observed and outlined, like forceful and aggressive transfers, no turning of bed-ridden patients’ bodies leading to untreated pressure ulcers, forceful feeding causing audible choking noises, and “patients observed crying for help with staff not responding for 30 mins to over 2 hours.”

One line in the memo notes that at Hawthorne Place Care Centre in north-end Toronto, there was one registered nurse on duty for up to 200 patients. The public was coming to realize that the horrific conditions at Quebec’s Residence Herron were not an isolated incident. The system — locally, provincially, nationally — was broken.

Reports since those early days of the COVID-19 pandemic have described a grievously ill-prepared elder-care sector. Picard describes public health officials scrambling to prepare hospitals for the incoming pandemic, but failed to properly equip long-term care facilities, calling them a “blind spot.”

Long before COVID-19 swept across the world in early 2020, Canada’s long-term care system was cracking under the strain of a growing population of residents, inadequate resources and insufficient investments.

Dr. Sinha of the National Institute on Ageing says the Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care has acknowledged that one in three residents in Ontario long-term care homes cannot afford the basic co-payments. And those who can must bunk up with up to three other residents if they want to save money rather than spend $88 a day for a private room.

Sinha said that not being able to afford even the least expensive option means there are a lot of Ontarians who have limited income sources and little to no savings. “It reminds us that, wow, when you think about one-third of people living in our LTC homes can’t pay the basic accommodation fee, that really speaks to the level of poverty that really exemplifies most people living in our LTC system,” said Sinha.

Of course, the more money a person is willing to spend, the more options there are available to them. A well-off patient may be eligible for home care with up to 24-hour private care every day from a hired live-in caregiver or a private homecare agency. Maybe, Sinha said, a patient lives in a retirement home instead, and pays more for extra visits from separate care providers.

“In other words, the richer you are the more options you have when it comes to long-term care,” he said. Sinha calls the long-term care system a safety net — a safety net that people have no choice but to rely on as they reach such a vulnerable phase of life.

Ontario has the highest percentage of private for-profit long-term care homes in Canada. This is significant, said Dr. Naheed Dosani, the founder and lead physician of Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless and an assistant clinical professor in the department of family medicine at McMaster University.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic it became clear that not-for-profit long-term care facilities had much improved outcomes such that the death rate was four times higher in for-profit long-term care homes versus not-for-profit long-term care homes. And why is that?” said Dosani, who is also a vocal advocate for a stronger long-term care system and founding member of Doctors for Justice in Long-term Care, a coalition of health care professionals founded during the COVID-19 pandemic to vocalize their frustrations over the system and its shortcomings. Dosani was possibly referencing a 2020 Toronto Star investigation, which found that Ontario for-profit nursing homes had four times as many COVID-19 deaths compared to city-run homes.

“You don’t get to say I want to line up for the not-for-profit or for-profit bed. It’s just the next bed available is what you get. It’s really like a lottery.”

Dr. Naheed Dosani

According to Dosani, the difference in quality of care between not-for-profit and for-profit long-term care homes is stark; not-for-profit homes measure much better in terms of quality of care. For-profit long-term care homes have a profit incentive to keep wages low for staff, resulting in high staff turnover rates, heavier workloads and ultimately lower quality of care. A 2019 report from the Ontario Health Coalition titled Situation Critical: Planning, Access, Levels of Care and Violence in Ontario’s Long-Term Care concludes that for-profit facilities “only spend 49 per cent of their operating revenue on staffing while not-for profits spend 75 per cent of revenue on staffing.” This ultimately affects the quality of care. The report goes on to reference a study that found that three months after admission, “the risks of mortality (for residents) was 20 per cent higher and the risk of hospitalization was 36 per cent higher in the for-profit long-term care homes when compared to non-profits.”

The question is, Dosani asked, why do governments like Ontario’s continue to support a form of care that supports profit over quality? “Should companies be able to make profit off the healthcare outcomes of elders? Especially in a system where you’re lining up for a long-term care bed, you don’t get to say I want to line up for the not-for-profit or for-profit bed. It’s just the next bed available is what you get,” said Dosani. “It’s really like a lottery.”

This was also the conclusion of a report published in May 2022 by Canadians for Tax Fairness. The report estimates that in recent years, for-profit long-term care corporations diverted $400 million annually away from improving care for patients, and instead pocketed the profits.

In Ontario, the provincial government provides around $6 billion annually in public funding to long-term care organizations, most of which are owned by private for-profit companies. One-third of that core public funding is classified as unrestricted, meaning long-term care operators choose how to spend it and don’t need to return any unspent money to the government.

“From a societal perspective, it begs the question of why we’re even put in (these) situations, why our society allows profit to be made off of people’s backs,” said Dosani. “What happens is, because that profit is not reinvested into long-term care, but actually just given to shareholders, as a result patients suffer.”

This is the same report in which Canadians for Tax Fairness estimated that if for-profit long-term care facilities had the same lower death rate as the non-profit facilities, at least 1,400 fewer residents would have died during the COVID-19 outbreaks of 2020.

Workers in these for-profit facilities were left with a limited budget, no paid benefits, no paid sick days, and often weren’t even able to get full-time positions. They had to work at multiple part-time jobs at different homes to make a living wage.

This current broken system prioritizes the warehousing of seemingly unwanted individuals, forgotten by society, rather than actually providing the conditions for a dignified life. “We’re essentially just warehousing frail seniors and people with disabilities, and that’s the plan. Just keep building more and more warehouses,” said Dosani. “It’s not feasible and it’s not meeting people where they are at… What we are doing is not working.”

My mind goes back to a day six years ago at St. Louis Residence. I sat across from my grandmother, holding her hand. I remember being surprised at the strength in her grip, belying her frail appearance. Every now and then she would murmur something under her breath.

I think our visits to that Orleans long-term care home had a deep effect on my father. After many trips to see my grandmother, he would look at me and say that’s no way to live. But it was his mother, we were maintaining a loving family link, and we always said, “that was nice,” after visiting her — because it was.

It was hard not to think about the other 197 people living in that home, so many so small and frail sitting in their respective wheelchairs, or lying in their own hospital beds, drifting in and out of consciousness and waiting for family to come visit, if they had any.

The needy poor of Ontario’s past and the roots of human warehousing

On a patch of land next to a freeway near Fergus, Ont., there are more than 270 bodies buried beneath carefully spaced spruce trees. The tall conifers are natural markers that replaced wooden crosses that rotted away long ago. Here rest the unclaimed remains of those who lived and died at the county poorhouse.

If you drive 90 minutes northwest from Toronto, you’ll find the historic town of Fergus. It’s surrounded by large suburban homes, but the main street through the town centre is lined with old stone buildings — erected by pioneering Scottish stonemasons — that have been gutted and repurposed into stores, restaurants and cafés.

Just outside of the town, up on a hill of mowed grass just a short walk from the spruce tree graveyard, sits an imposing three-storey building. A burgundy roof caps square, grey stones, and a flight of steps leads up to the double doors of what used to be the entrance.

This building was once the Wellington County House of Industry and Refuge, a shelter for the local homeless and impoverished where they could exchange their labour for room and board. In 1947, all houses of industry in Ontario became homes for the aged and provided care for the elderly and infirm.

In Wellington County, a local bylaw established how the original house would be organized. It outlined the rules for the home, who was responsible for decision-making (a committee acting on behalf of county council), who the inspector was, and a protocol for visits from a physician. It is outlined in this bylaw that the physician, for example, would examine inmates to make sure they were not “feigning illness to get out of work.”

“There was this whole perception that society had: ‘Were you really poor? Were you really unable to work? Or were you just lazy?’” explains Hailey Johnston, curator at the Wellington County Museum and Archives, which occupies the same imposing building that was once the House of Industry. “This was definitely a stigma that — I mean we see it right in the bylaw, the fact that this was written in tells you how common a thought that this was,” she says.

According to Johnston, the Wellington House of Industry and Refuge is the oldest remaining rural home of its kind. It opened in 1877 and then changed to the Wellington Home for the Aged in 1947 after provincial legislation required every Ontario House of Industry to do so. The home then lasted until 1971, when it closed and moved its residents to a newer, modernized facility nearby. The building then became the Wellington County Museum and Archives.

Johnston uses the phrase “worthy poor” to describe the attitude of governments of the day towards those living in poverty. To attain the services meant for the truly needy, one needed to have been genuinely unable to work, rather than just declining work for unspecified reasons. “That is exactly the mindset of the time — and really you would argue that not a lot has changed in many cases,” Johnston said. “That goes to the root of the name, The House of Industry and Refuge. Industry comes from this concept of, ‘You don’t want to be the idle, lazy poor.’”

The houses of industry were meant as a remedy for the poor. It was thought that strict living and hard labour would help them. “Part of the reason people thought these people were suffering from poverty and they needed help was because really they weren’t leading good lives and they needed rules, they needed order to help them and improve themselves,” Johnston said.

It soon became clear that many “inmates” (as they were known) would not be leaving the Home, most of the time because they genuinely were unable to. They might have had nowhere else to go; or they might have had health problems that were poorly understood at the time, preventing them from working.

Living conditions in the Home are described as “Spartan.” Men and women were segregated, with each group sleeping in the same room on cots. There was an outhouse detached from the main building where, even in winter, frail, elderly inmates would need to walk outside alongside the barn to get to it. Despite being admitted into the Home for being unable to work, many inmates were expected to partake in hard labour. The Home was a working farm and intended to be self-sufficient.

“The purpose of the Home is to provide a congenial atmosphere for the old people to spend their remaining days.”

Dr. John H. O’Brien, 1940 annual report on the Wellington County House of Industry and Refuge.

In 1909, the Matron of the Wellington House of Industry and Refuge, Matron Griffin, gave a speech at a conference for managers of houses of industry. In the address, she advises that matrons and keepers vary the routines, diets and activities of inmates and provide entertainment to avoid a prison-like atmosphere. “A matron must be a strict disciplinarian,” she stated, “but kind hearted and sympathetic and at all times most cheerful with the inmates, acting as a foster mother of a large family who are dependent on her sympathy, advice, and assistance.”

“You can sort of come to your own conclusions that it was sort of a balance between what society thought was best, what the taxpayers thought was best, and what the actual individuals running the homes thought was best for the people,” said Johnston.

Some of the people advocating for change were the physicians at the Home. In the Wellington County Archives were found reports from the Committee of Management of the House of Industry and Refuge, addressed to the Council of the County of Wellington. In these documents there are recommendations to improve the effectiveness of the Home. In one of the reports from 1940, Dr. John H. O’Brien, the dedicated physician of the Home, writes that, “the purpose of the Home is to provide a congenial atmosphere for the old people to spend their remaining days.” So it must have been understood that many patients were never going to leave the Home.

And later the same doctor, in a 1946 report, would call for council to create more space for the overcrowded patients. A space “should be made for hospital care of old people with chronic conditions. Hospitals are intended for acute illnesses and they are loath to admit patients who will probably spend years in them as patients.” At the time it was standard for patients of the Home to be transferred to the Fergus Hospital for any care. But here we see a distinction between hospital care and what Dr. O’Brien is requesting: an in-house form of continual care for ageing residents.

Ontario’s eventual system of long-term care was edging into existence across the province in places like the Wellington County House of Industry and Refuge.

There was a hospital wing built in 1893, but frequent overcrowding and a lack of staff with actual medical training rendered it less than effective. It was Dr. Abraham Groves, the physician in charge before Dr. O’Brien, who first advocated for the building of a hospital wing. “It was clear to him at the very start that this couldn’t just be a place for people to go where they didn’t have a place to live,” Johnston said. “These were people with very real medical needs.”

The Home wasn’t initially designed to have the space for hospital facilities. And it was almost always the matron, the wife of the keeper of the Home, who would treat inmates to the best of her ability. But according to Johnston, there were many inmates who required care beyond the skills of the matron and beyond the capacity of the house of industry to provide proper care for.

Over time, it was gradually realized that the majority of the inmates at the Wellington County Home were elderly. For Johnston, this was a natural evolution. As time went on, other institutions popped up. “Children were no longer in the house after the Children’s Aid Society network was started up,” Johnston said. “It’s almost like in the beginning the house of industry could be seen as more of a catch-all for any number of reasons someone may need help. But over time, it really became that the majority of people who were in these institutions were the elderly.”

Then, in 1947, every house of industry in Ontario formally became a home for the aged thanks to the Homes for the Aged Act, 1947. L. Earl Ludlow was named the first director of Homes for the Aged in Ontario, and according to Norma Rudy — a historian who details his exploits in her book For Such a Time as This — Ludlow made it his mission to improve the conditions in every single home for the aged in Ontario. His guiding philosophy was simply asking: “Would I like this for myself? Would I like this for my mother?”

In striking similarity to the present day, Ludlow would shine a light on the “deplorable conditions, the overcrowding and the need for change” in an attempt to sway his superiors. Ludlow also outlined how social pressure would increase in the future due to growing numbers of elderly who would be frustrated with “the overcrowded decaying system.”

This social pressure of an ageing population is once again at play in 2022. And that social pressure creates political pressure, said Dr. Sinha of the National Institute on Ageing. “Soon, by 2031, one in four Ontarians will be an older person,” he said. “That’s a lot of voters who are older and who are going to be demanding that there needs to be better support for them.”

The poorhouses of 150 years ago are the ancestor to the modern long-term care home. The concept of warehousing vulnerable people comes directly from those former houses of industry, like the one next to the spruce grove cemetery on a hill outside Fergus.

“The people who would have ended up needing assistance 150 years ago, those types of situations are still around today,” said Johnston. “The fact that we still have those problems suggests that part of the solution isn’t just figuring out what we’re going to do in terms of long-term care, welfare and different social assistance programs. But I would hope someday doing a better job of helping people with their lives before they get to this point where they need a little bit more care.”

The memorial recalls the hundreds of people who had once climbed up those stone steps to the poorhouse. Some would leave if they were able to, and some of those would surely have returned. And most would stay there for the rest of their lives.

Breaking free of the ‘bear trap’ of inhumane elder care

My grandmother, Simone, was French-Canadian from Manitoba. We called her Gramere – an anglicized version of the French word for grandmother. I always felt guilty about not visiting her enough when she was at the residence home, and then later when she was at St. Louis Residence long-term care home in Orleans.

I hated that place. I hated it and I only visited it for an hour or two at a time. The average stay for Canadians at a long-term care home is 16 months. Long enough, one could imagine, for the stay to become torturous.

Canada’s ageing population is growing, and the current system in place – one that comes from a tradition of warehousing dependent elders, stowing them away in institutions – is not meeting the needs of some of society’s most vulnerable. We are at a tipping point, one that has been approaching for decades. “I do think the next 10 to 20 years will be quite crucial in terms of how we start thinking about where we need to move forward,” said Dr. Sinha of the National Institute on Ageing, one of the many institutions trying to advocate for newer ways of thinking about elderly care.

“We don’t even value older adults, and when you don’t value older adults to begin with, why would you even start ‘wasting’ precious taxpayer dollars on trying to provide that support?”

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research, National Institute on Ageing and director of geriatrics at Mount Sinai and the University Health Network Hospitals, Toronto

In some European countries like Denmark, Sinha says they take a great deal of pride in their ability to provide dignified care and support to their ageing population. The difference is striking. “It’s just really astounding when you see a completely different mindset, a completely different level of funding and support and even the approach to shelter, accommodation, care, funding,” said Sinha. “It’s all based on a fundamentally different set of values than the values that have underpinned the creation and sustenance of long-term care in Ontario and across Canada.”

Overall, Canada spends a lot on healthcare compared to the rest of the world, said Sinha, but its percentage of healthcare spending as it relates to long-term care is lower compared to countries like Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canada is one of the countries that spends the most on health care. In 2019, Canada spent 10.8 per cent of its GDP on health care, ranking fifth among OECD countries. In a report from the OECD on total long-term care expenditure in 2018, Canada ranks twelfth, spending just under two per cent of its GDP on long-term care. Countries at the top of the list like Netherlands, Denmark, Norway and Sweden spend between 3.5 and 4 per cent of their GDP on long-term care.

And this lack of proportionate funding is a symptom of longstanding societal ageism, according to Sinha. “We don’t even value older adults, and when you don’t value older adults to begin with, why would you even start ‘wasting’ precious taxpayer dollars on trying to provide that support?” said Sinha.

In the Netherlands, a new style of nursing home was developed, called the Hogeweyk Dementia Village. It claims to deinstitutionalize the traditional nursing home, reimagining it as a neighbourhood with houses, pubs, restaurants and a supermarket. This allows residents to wander freely and interact with the micro society around them, rather than being confined to rooms in a hospital-like facility.

In Canada, this model has inspired the organization Providence Living – a not-for-profit healthcare organization – to build the first publicly funded long-term care home based on the Dutch concept. The new home will be called Providence Living Place, Together by The Sea. The organization broke ground in British Columbia in spring 2022 and already has plans for a second home in the province.

The fact that this is the first publicly funded dementia village concept home is significant, said Candace Chartier, who was the president and CEO at Providence Living for the development and strategic planning phases of the project. At the time of the interview for this report, Chartier was still leading the Providence initiative but has since stepped away, returning to Ontario to act as primary caregiver for her own ageing family members.

In a public statement, Sandra Heath, board chair at Providence Living, said Chartier’s impact as CEO was significant. “Thanks to her network and vision, we are considering new services that will benefit people as they move through the different chapters of their lives and will complement our new model of care.”

In our conversation, Chartier was indeed excited about this new model of care and the apparent support from the British Columbia government: “The B.C. government and all of our stakeholders have seen that this is a really important priority to move towards a different type of long-term care,” Chartier said. “And I think that’s key because of the impact it’s going to have on seniors and what the whole structure and approach to changing the model of care is going to be.”

Chartier began her career as a registered nurse, graduating and specializing in emergency and surgical care. “When you go for an RN, there are two specialties that you apply for for your consolidation, and so I wanted to be ‘super-nurse’,” Chartier said. For the first five years of her career, she worked in different areas of acute care and then shifted to delivering air ambulance service in Northern Ontario, flying north of the tree line to various Indigenous reserves.

In 1995, there were actually too many nurses – which Chartier joked you’ll never hear of ever again – and she moved back to Southern Ontario to discover that the only jobs were in long-term care. “I applied to long-term care and I absolutely fell in love with it. I fell in love with the seniors. These are our history makers. This is why we are who we are and what we have today,” Chartier said.

Chartier spent the last 30 years employed in long-term care, working her way to leadership roles at Southbridge Care Homes, the Ontario Long Term Care Association and Safe Haven Consulting before leading Providence’s push to pioneer a new way of accommodating Canada’s elderly population.

Looking back over the years, Chartier said long-term care has changed immensely. “The difference between 30 years ago and now is, there is so much more legislation, so there’s so much more administrative burden, there’s so much more public scrutiny, because of events that have happened,” Chartier said. “It’s just a different world nowadays. And 30 years ago, you didn’t have to worry about a shortage of staff. And now you’re lucky if you can keep staff in the building.”

Providence Living Place, with its European concept, hopes to change the way ageing adults live and, Chartier hopes, change how long-term care is perceived.

“The public thinks long-term care is the bad guy and it’s been a negatively connotated environment really for the last four or five years, with those key events that have happened,” Chartier said, referring to the COVID-19 pandemic and other long-term care revelations, such as incidents of neglect and abuse.

“So people haven’t forgotten. If anything, COVID exacerbated it because of all the people that died and how fast they died.”

“The whole model of care concept is going to change, as well. That means changing the work streams, changing the policy, the procedures — like everything.”

Candace Chartier, former CEO, Providence Living

Sinha is cautiously optimistic about this new home. “If you actually look at the plans (for the BC dementia village homes), it looks like a large long-term care home, but they’ve been able to design it with an inner courtyard,” Sinha said. Sinha’s point about the difference between a “gimmick” and a “fundamentally different” form of care is key: “We have to remember,” he says, “that there’s one thing about the physical structure of these homes, it’s another thing to…look at how care is actually provided and ask if it’s being provided in a truly dementia-friendly way.”

Chartier was adamant about the new home being a significant transformation of care. She said Providence Living is working with a group out of the Netherlands and taking pieces of what they have been doing for over 20 years and customizing that into a new program. The new model, she insisted, goes far beyond superficial changes to the physical space and encompasses the entire philosophical approach to serving residents, Chartier said.

“You have to remember, 90 per cent of people living in Canada’s LTC homes currently are living with a cognitive impairment and two-thirds are living with dementia,” Sinha said. “So all places should be designed to be dementia-friendly environments, as opposed to say purpose-built dementia villages.” Despite the name “dementia village,” Chartier said the home is for seniors with a variety of needs. Which is why, she said, it’s important for them to say “based on the concept” of a dementia village rather than conforming precisely to the Dutch model. The central concept, though, is the facility’s appearance and its functioning as a self-contained community.

But Sinha highlights the challenges of being publicly funded. “They readily admit that they are dependent on what the government will give them for the actual construction cost, and it’s not necessarily the budget they would have wanted to create ideally what they needed to,” Sinha said. “But I think fundamentally, this idea of a dementia village is just another form of creating more dignified long-term care spaces.”

The official cost for Providence Living Place was set at $52.6 million. The British Columbia Ministry of Health gives out awards for the development of long-term care beds through various projects. According to Chartier, no province has ever given out an award like the one Providence Living received to build its neighbourhood-style residence based on the concept of a dementia village. And Chartier said they have all the support they need. “It was a significant amount of money, almost to the tune of $53 million. That’s why it’s so incredible, and they fully support the new concept that we’re doing. And a big piece of this concept is going to be model of care,” Chartier said, once again emphasizing that this new model is going to be the province’s go-to approach to elder care moving forward.

“I think we need to change the dialogue surrounding long-term care,” Chartier said. “We have to show people that it’s not the scary place that it’s made out to be.”

But for many, in reality, it is still a scary place — especially for members of marginalized groups. That’s the issue that research fellow Ashley Flanagan works on at the Toronto-based National Institute on Ageing. Specifically, Flanagan focuses her research on how 2SLGBTQI folks experience forms of care as they age and what their concerns are.

Flanagan, who completed her PhD in ageing, health and wellbeing at the University of Waterloo, first became interested in this work during her Master’s research on experiences in caregiving. There, she spoke with some older 2SLGBTQI people about ageing in the current system. “That really flipped this switch for me and started me thinking about my own ageing as a queer person as well,” Flanagan said. “Hearing their fears and thinking like, OK, what can we be doing to not only make things better in the present moment, but also for myself and my friends and family as we all age.”

According to Flanagan, generally, ageing people who identify as queer or trans or two-spirit often fear that they’ll have to “go back into the closet” when it comes to accessing elder-care services, and so they’ll have to hide aspects of their identity. And if they are moving into a new space – like a long-term care home – they feel this suppressing of their identity will affect new relationships that they are forming.

Flanagan said this can occur “out of fear that if they share those aspects of their identity with the folks providing care that they are not going to get the level of care that they deserve. Because historically when we think about healthcare, there has been a lot of discrimination and refusal to provide care by care providers out of fear, out of not knowing, out of not taking the effort to look into ways to better support 2SLGBTQI+ folks in general,” Flanagan said.

Earlier in her career, Flanagan had the opportunity to speak with an older trans woman. She shared with Flanagan that one of her biggest fears was that she wouldn’t be able to care for herself one day and that she would need to access services through a long-term care home. The trans woman was scared that she wouldn’t get the care she deserves because her identity as a woman wouldn’t be respected.

“There is a movement to rethink the standards of long-term care that is taking the resident-centred approach — putting the individual at the centre of care.”

Ashley Flanagan, PhD, research fellow, TMU’s National Institute on Ageing

“She was afraid the things she does for herself on a daily basis in terms of her physical appearance and the way that she dresses wouldn’t be respected,” Flanagan said. “And rather than go that route, she just wouldn’t face it. Not to put it delicately, but she told me she would rather die than go into long-term care.”

At that moment, Flanagan was heartbroken. She began to think about the spaces she had been working in, the spaces that were supposed to help people, supposed to be a positive option. “In that moment is when I took up the cause and really made it my goal to be that advocate for that change, so somebody doesn’t have to make that decision,” Flanagan said.

“That was one of the stories that really just drives me forward because that shouldn’t be someone’s outlook on their future.”

Flanagan thinks a change is necessary in the ageing care sector, and she believes there is an opportunity now. “There is work being done. There is a movement to rethink the standards of long-term care that is taking the resident-centred approach — putting the individual at the centre of care,” Flanagan said.

A large part of what Flanagan advocates for, and what she has learned through her qualitative research, is the importance of seeing individuals as people, not just bodies. “When we start to move out of that medicalized lens, we start to see folks and the way they interact as more of a network,” Flanagan said. “We start to see folks in a more holistic way. We bring empathy and recognize intersectional identities so that we can better support them as individuals with various and unique needs.”

This approach might become manifest by including spaces in long-term care homes that specifically welcome and encourage 2SLGBTQI folks to live there. It includes what Flanagan calls an emotion-centred approach to care – where care providers are very intentional with how they interact with patients on the receiving end of assistance. This involves “not only taking into consideration their physical needs,” Flanagan said, “but also taking into consideration their emotional needs, their spiritual needs, and their need for connection.”

There’s an emphasis on care providers spending time to get to know the person that they are caring for, rather than having to rush through care in order to meet quotas or deadlines. “When we think about long-term care, time is often in short supply because there are issues around staffing levels or funding. There are all these issues that really impact the way that folks are able to interact in a care environment,” Flanagan said.

But already, the Ontario Centres for Learning Research and Innovations offers resources that long-term care homes can use to facilitate this organizational culture change that Flanagan and others are advocating for. The OCLRI, a partnership of three long-term care research centres in Toronto, Ottawa and Waterloo, provide resources to managers of elder-care residences to help them revise their policies to ensure that they’re inclusive and affirming for both residents and staff. The idea is to ensure these facilities offer a wide range of programming for residents so they can see themselves — their identities and pastimes and passions — reflected in the daily life of a long-term care home.

“That’s the number one thing at this point in the journey towards that inclusive and affirming care — raising our levels of knowledge and raising our levels of awareness that 2SLGBTQI+ folks do get older and they do require care, and varying levels of care and support,” said Flanagan.

“We need to have a societal shift in how we look at ageing, because otherwise we’re never going to get out of this bear trap that we’re in.”

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research, National Institute on Ageing and director of geriatrics at Mount Sinai and the University Health Network Hospitals, Toronto

This transformation of care would ideally allocate more time to building relationships between care providers and patients. “It reintroduces a little bit more of the humanity into care,” is how Flanagan puts it.

Sinha said societies around the world that do a better job of caring for older adults are ones that value them as human beings who truly remain net contributors to the wider community as they age. “I think those societies that view older people as disposable, as no longer worth time and investment, tend to have much poorer elder care systems,” Sinha said. He says he’s seen this pattern over and over around the world. “It reminds me that we need to have a societal shift in how we look at ageing, because otherwise we’re never going to get out of this bear trap that we’re in.”

When my grandmother passed away, we went to the end-of-year service that the long-term care home held to remember all residents who had passed away over the past 12 months. It was winter and we huddled together in the large, modern-looking chapel. A slideshow on a projector screen above the daïs showed the names of the residents who had died that year.

There was a Christmas tree in the corner. Christmas carols were sung and prayers I didn’t know the words to were read. Looking back now, I imagine all the families who were invited to that service, all the sons and daughters and grandchildren who had no other option but to place their loved one in such a facility — a place outdated in concept and inadequate in its service provision, but which continues to be the primary method for housing our elderly.